THE BOND BETWEEN CAMEL-DRIVER AND CAMEL

The camel-driver on march is an interesting subject

of study. There is between him and his beast of burden a bond of

affection hardly less strong than that which exists between the Arab

horseman and his steed. The camel is the essential of life in the sands.

Travel and trade are dependent upon him.

On march the camel goes best when his driver sings.

These songs, or chants,

(p255)

almost invariably concern the virtues of the ungainly but intrepid

beast. His praises are sounded in most extravagant terms, and the animal

seems to like it.

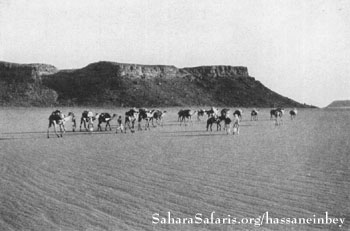

APPROACHING

THE HILLS OF OUENAT

Ouenat was found to be an oasis with 150

part-of-the-year inhabitants (see text, page 275) [photo page 256]

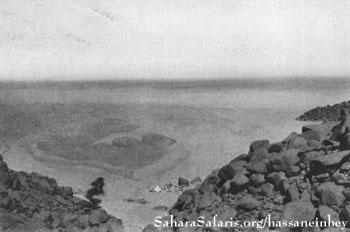

THE DESERT AS

SEEN FROM THE HILLS OF OUENAT

The white spot is the author's tent,

which was not often set up, as it was very difficult to raise (see text,

page 245) [photo page 256]

ONE OF THE

WELLS AT OUENAT

There are two types of wells known to

the desert—the ain, which is a natural spring, and the bir,

whose existence is usually indicated to the traveler by damp sand, where

he may dig and find water. These natural basins of Ouenat, which contain

rain water, are not, strictly speaking, of either type, but they are

called ains. [photo page 257]

THE CARAVAN

APPROACHING THE OASIS OF THE OUENAT

The enormous boulders of the precipitous

cliff have been worn smooth by the sand-blasts of the desert (see text

page 275) [photo page 258]

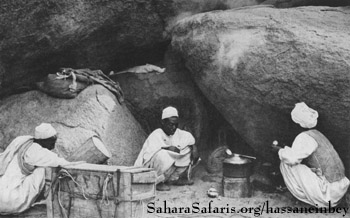

A CAVE

UTILIZED AS A KITCHEN FOR THE CARAVAN DURING ITS STAY IN THE OASIS OF

OUENAT

Beneath the shadow of these rocks the

members of the caravan found some relief from the blistering heat of the

outside world. [photo page 259]

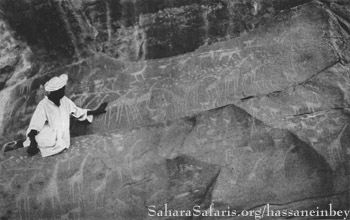

THE

MYSTERIOUS ROCK CARVINGS AT OUENAT

Hidden in the heart of this

hitherto-unknown oasis are these strange

pictographs. Who carved them

and when are questions yet to be answered by science, but there are

indications that they may antedate the Christian era (see text, page

276) [photo page 260]

THE WATER

SUPPLY FOR THE CARAVAN

An average water-load for a camel on

march is four sheepskins, each containing six gallons. [photo page 261]

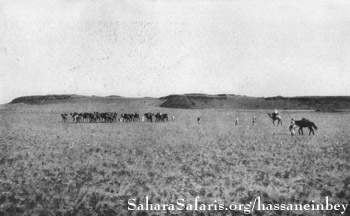

THE CARAVAN

APPROACHING ERDI: THE COUNTRY CHANGING FROM ARID DESERT TO A PLATEAU

COVERED WITH GRASS

This was the most interesting change

encountered in the Libyan Desert. It marks the line between the

waterless waste and country with sufficient grass for pasturage. Had the

expedition not come across this grass, the entire caravan would have

been lost [photo page 262]

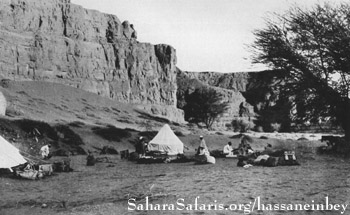

CAMPING IN

THE VALLEY OF ERDI AFTER AN 11-DAY TREK FROM THE OASIS OF OUENAT

The sheer walls inclosing this oasis are

of red rock, and the sands of the floor are likewise red. Note the

author's horse, Baraka, in the shade of the trees at the right. [photo

page 263]

THROUGH THE

VALLEY OF ERDI

While there remained many miles of

travel for the expedition after reaching this valley, the long,

waterless desert treks were at an end. The march to El Obeid was by easy

stages, through fertile country, from village to village (see map, page

236). [photo page 264]

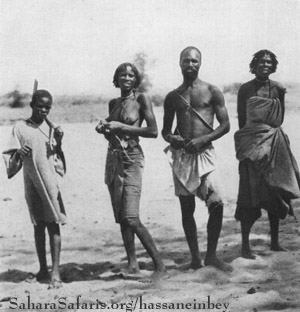

SONS OF GORAN

CHIEFS AT AGAH, BEYOND ERDI

One of the kindliest and most hospitable

natives encountered by Hassanein Bey south of Kufra was a chief of this

tribe residing in the Oasis of Ouenat. He was known as Sheik Herri, King

of Ouenat. [photo page 265]

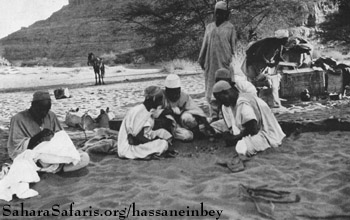

THE MEN OF

THE CARAVAN PLAYING DRAUGHTS ON THE SAND

The checkerboard is made by pressing

holes in the sand with the fingers. Black and white stones are used for

the "men." [photo page 266]

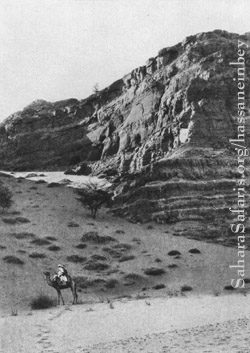

DIFFICULT

COUNTRY THROUGH WHICH THE CARAVAN PASSED BEYOND ERDI

This is the worst type of country

imaginable for both beasts and men, as the sharp stones cut the padded

feet of the camels as well as the thin-soled shoes of the men. Travel by

night over such land is practically impossible. [photo page 267]

A BIDIAT

FAMILY

From right to left, the mother-in-law,

the husband, the wife, and the son. [photo page 268]

[photo]

(p256) [photo]

(p257) [photo]

(p258) [photo]

(p259) [photo]

(p260) [photo]

(p261) [photo]

(p262) [photo]

(p263) [photo]

(p264) [photo]

(p265) [photo]

(p266) [photo]

(p267)

The camel-driver knows his charge so well that he

is able instantly to identify the beast by its footprints in the sands;

and not only is he able to do this, but also to identify the son of that

camel; in other words, it would seem that each camel family has its own

footprint peculiarities.

The average animal will carry a burden of from 250

to 300 pounds, but it is the duty of the astute explorer to supervise

the loading at the beginning of each march, seeing always that the

camel, which carried a heavy load yesterday is given a light burden

to-day.

Where supplies are plentiful, the animals are given

grass and barley, but in desert trekking, when these are not obtainable,

they are fed twice a day on dates, a meal consisting of as much fruit as

can be gathered together twice in two hands. The animals are serviceable

up to 23 or 25 years of age and are valued at from $50 to $100.

It is recorded that, when water supplies have been

exhausted, caravan leaders

(p268) have slain their

weaker camels and the drivers have then extracted all the moisture

possible from the stomachs of the animals. In the final extremity, the

frothy pink blood has, in some instances, been drunk; but this practice

inevitably means the end, for such a draught is comparable to the

drinking of sea water by shipwrecked persons.

(p269)

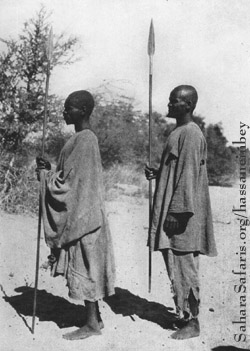

TWO BIDIAT

MEN

"The southern portion of the 1ibyan

Desert is inhabited by tribes of blacks—Tebu, Goran, and Bidiat—who are

rather more refined in features than the central African negroes" (see

text, page 234). [photo page 269]

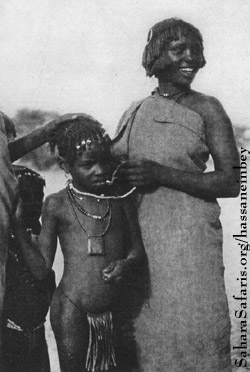

A BIDIAT GIRL

WITH HER SISTER

The child is wearing a macaroni

necklace. The author gave the natives macaroni to eat, but they quickly

converted it into "jewelry." [photo page 270]

In winter, in case of necessity, a camel in good

condition can go for 55 days without water; in summer, from 10 to 12

days is the limit.

If an animal becomes completely exhausted on a

trek, it must be killed. This is one the saddest experiences of the

desert, for a camel is really a member of a caravan and not merely a

beast of burden.

|